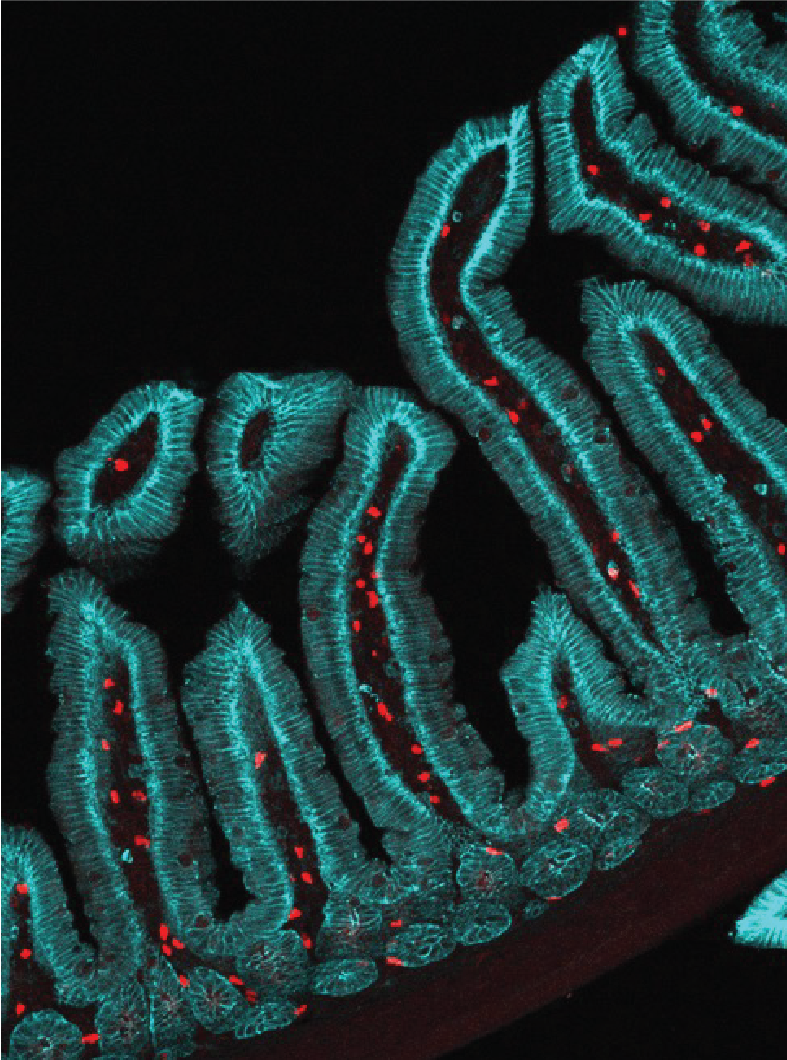

Caption: Image of IL-5+ reporter cells along the crypt-villus axis.

Caption: Image of IL-5+ reporter cells along the crypt-villus axis.

By Asher Jones

One morning in 2020, Victor Cortez injected mice with a protein called IL-25. Typically, he would wait 50 days before measuring the effects of the treatment on gut epithelial cells. But due to COVID-19 lockdowns, Cortez, like many researchers, had to put his research on hold.

Six months later, Cortez finally got permission to reenter the lab to complete the experiment. Taking one of the injected mice and a control counterpart that hadn’t received IL-25, he was shocked to notice dramatic differences between the two animals. The control mouse had the normal pudginess of an animal its age, while the IL-25-treated animal was slender with sleek, shiny fur.

“The mouse I had injected with IL-25 looked like it was only about six weeks old, not six months,” said Cortez, who was a postdoc at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) at the time. “I thought I must have picked a mouse from the wrong cage.”

But it was the right mouse. The IL-25 injection seemed to cause broad physiological and metabolic changes in the animals.

Cortez, who joined the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Immunology, in September 2025 as an assistant professor, was studying IL-25 in the context of helminths—parasitic worms that cause intestinal infections that are very common worldwide, especially in communities with poor sanitation.

During helminth infection, tuft cells in the gut release IL-25, which activates a type of innate lymphoid cell (ILC) called ILC2. ILC2s produce IL-13, which boosts mucus production, forming a protective barrier that can help expel parasites and protect the gut against subsequent infections.

Cortez sought to understand the longevity of this immunity and identify the cells and pathways that control it. In a new paper published Sept. 5 in the journal Cell, Cortez and his colleagues at UCSF found that IL-25 injection led to changes in the gut lining and lengthening of the small intestine, which lasted for at least 50 days and improved resistance to helminth challenge.

These gut adaptations were driven by a novel population of ILCs—which Cortez named effector-memory ILC2s. The researchers found that the cells remain activated long after helminth infection or IL-25 treatment.

And, strikingly, the beneficial effects of IL-25 weren’t limited to the gut. Cortez and his team also detected effector-memory ILC2s in fat tissue and the lungs of mice, and these animals were more resistant to infection with the bacterial pathogen Salmonella and had improved recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“We were surprised to see the multitissue effects of these cells,” said Cortez. “All of the challenges we threw at mice treated with IL-25, they were better off. They had better mucosal immune responses to all kinds of different pathogens.”

And those svelte mice from Cortez’s pandemic experiment? The researchers showed that rodents treated with IL-25 had reduced weight gain and less fat tissue than untreated mice, suggesting that IL-25 could influence metabolism.

According to Cortez, this research ties into the “hygiene hypothesis,” the idea that certain modern diseases such as allergies, asthma and autoimmune conditions may stem from reduced exposure to microbes and helminths. Stimulation of the immune system by parasitic infection can improve some aspects of host health.

“I think about IL-25 as ‘the hygiene hypothesis in a can,’” said Cortez. “It’s a really broad hypothesis with a lot of elements to unpack, so identifying IL-25 as a single molecule that is turned on by parasitic infection and stimulates broad mucosal immunity gives us a system to answer some long-standing questions about this hypothesis.”

At Pitt, Cortez’s initial research will focus on the molecular underpinnings of immune memory in effector-memory ILC2s and how they coordinate resilience to multiple types of pathogens in different tissues. He will also delve deeper into the finding that IL-25 influences metabolism and explore the potential of immunotherapy-based approaches to obesity treatment.

“Immune cells are part of an ecosystem,” said Cortez. “Each cell is like a different animal on the African savanna that is part of a larger community. To truly understand one type of cell, you have to look at how it’s interacting with other tissues as part of that wider system.”